Serving Infants, Toddlers, and School-aged Children During COVID-19

It is late into the night when Sue Carrera, a licensed family child care provider of 13 years in Inglewood, is done with the deep cleaning, disinfecting, and preparation for the next day. It has been an exhausting eight months. In mere hours, at seven the next morning, Sue will welcome 11 children into her home. She does so willingly, but cautiously because her 81-year-old mother also lives with her. Fortunate to have remained open, Sue is dedicated to serving the children and their families, but also wonders if this is sustainable.

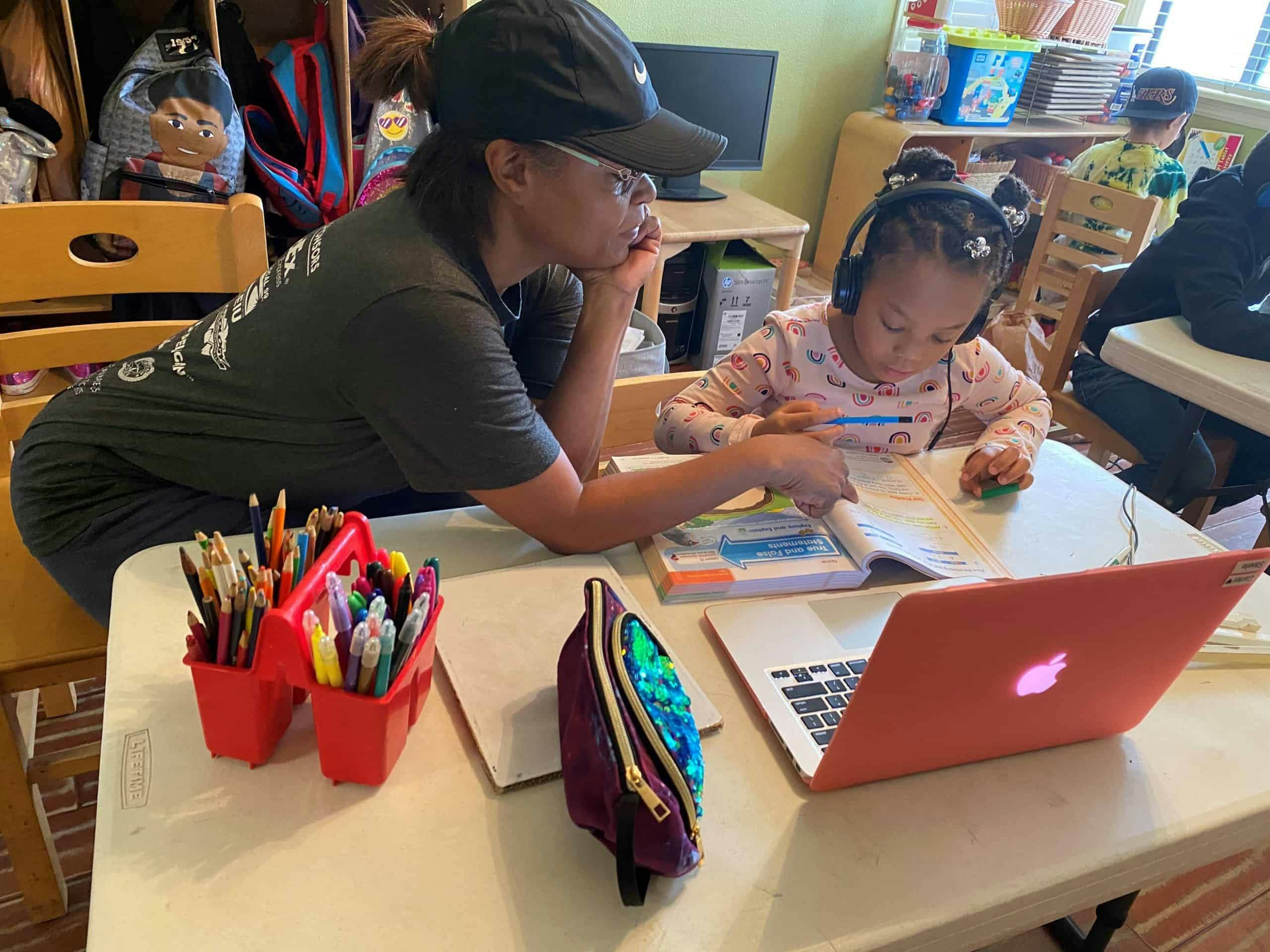

Before COVID-19, Sue worked mostly with children under the age of four. Now she also serves five school-aged kids, from different districts and from schools with different schedules. Sue is intentional about meeting the needs of each child under her care, but it isn’t easy.

Sue has taken on the role of parents/families supporting children during distance learning, all without additional training, resources, or compensation. She does her best to figure out when students need to log in, problem-solve forgotten passwords, connect with teachers daily, and work through ongoing technical glitches without clarity on how to access assistance. She bought headsets and had to create a separate space so the school-aged kids can all be logged on to their laptops, separated from the infants and toddlers.

Supporting infants, toddlers, and school-aged children simultaneously is both complicated and taxing. Sue is hungry for clear guidance and technical assistance as she implements the constantly evolving protocols designed to protect everyone. She works hard to stay informed, but timely access to information is not easy. “Community Care Licensing sends out emails, but if you are not computer savvy, or on their list, there would be no way to know the latest information on available guidance, supports, and stipends,” she noted.

Working with infants and toddlers looks very different with COVID-19 guidelines and Sue grapples with how to implement them. Toddlers no longer have their own classroom time. Her youngest learners spend most of their time in the open space, where they now find their toys, activities, bottles of hand sanitizers, and soap. How can she rearrange the learning space to encourage six feet of social distancing with little ones who want to touch everything? How can she allocate toys and materials so they can be cleaned and disinfected after each use and not going from the mouth of one child to another?

Increasing cost pressures have also been challenging. Daily deep cleaning has increased expenses dramatically. Her grocery costs alone have doubled to provide school-aged kids three meals a day. All expenses are out-of-pocket and put on her credit card. SEIU Local 99 provided Sue with information to access stipends for supplies. Sue is grateful for what she can receive, but the costs keep coming. While Sue is paid for each child, current rates do not fully cover the cost of care. As an example, for one infant she receives $232 per week. Considering infant care takes 10 hours minimum per day and 50 hours per week, her pay comes down to only $4.64 per hour.

Despite the growing workload, Sue recently had to make the hard choice of letting go of one of her two assistants or asking them both to take a pay cut from the $13.50 per hour they receive—which she already knows is not enough pay. She chose to cut her staff, but the cost reduction isn’t enough. Sue is currently not taking pay for herself, like many other child care providers facing these same realities.

Despite growing research on the importance of the first five years, the early childhood field has been neglected when talking about education. Home-based providers, in particular, who are predominantly women of color, have long been overlooked and underfunded. To address the historical neglect of this field exacerbated during COVID-19, providers like Sue need:

- Increased funding to maintain the pay and support of assistants, who serve the different groups of children in their care.

- Support to engage in partnerships with schools that ensure ELC providers have the resources and technical assistance needed to adequately assist school-aged children engaged in distance learning.

- Access to free and reliable internet, especially when multiple children are online for class.

- Continued reimbursement to keep ELC providers open and solvent as public health guidelines restrict the number of children they can serve or if providers need to close due to COVID-19 exposure.

Access to quality child care is the foundation that allows working families and the economy to survive; it is also the foundation on which we will thrive beyond this crisis. Providers have been the essential workers at the forefront of COVID-19 and deserve recognition and investment.

Advancement Project California launched our early learning and care blog series to show how California has the opportunity to take bold steps to build an early learning and care system that addresses the foundations of systemic racism, racial equity, and economic justice. Read more below, and check back daily through January 29th for new updates.

- Tracing the Roots of Systemic Racism in the US Early Childhood System

- Saving What Is Left of Early Childhood

- Daily Reality of Home-based Child Care Providers During COVID-19

- Quality Learning and Care that Women of Color Providers Bring Amidst COVID-19

- Serving Infants, Toddlers, and School-aged Children During COVID-19

- Jumping Hoops and New Ways to Show Love

- The Necessity of Staying Open During COVID-19

- Navigating an Uncertain Reality

- I Am Whole

- State and Local Resources to Support Early Learning and Care

- In-depth Supplement to the Essential Workers to the Essential Workers Blog Post Series