Tracing the Roots of Systemic Racism in the US Early Childhood System

In 2020, we witnessed the disproportionate health and economic burdens of COVID-19 on communities of color and the persistent violence of police brutality against Black Americans. These crises call on us to examine how systemic racism impacts communities.

Early learning and care programs (ELC) play a vital role in promoting healthy child development, setting children on a path toward success. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored that ELC is an indispensable part of supporting families and the economy. A thriving ELC field is essential to the state’s recovery.

The pandemic deepened the inequities children, families, and early childhood providers and professionals of color face, raising the stakes for policymakers to act swiftly to address racial inequities in the ELC system—this requires a look back at the roots of systemic racism.

Undervaluing the Early Learning and Care Professionals from the Start

Black women historically bore the burden of domestic work, including early childhood, first as forced labor while enslaved and then as an underpaid labor force.1 After abolishing slavery, women of color, including Black women, continued to make up most of the domestic workforce, as one of their only economic opportunities.2

In 1938, federal lawmakers enacted exclusionary rules in policies like the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) that ensured second-class treatment of the predominantly Black agricultural and domestic workers—including child care providers.

ELC professionals have never received fair pay or support reflective of their value and expertise. Today nationally, the ELC workforce made approximately $14.38 per hour, with women of color making even less: Black women made $12.98 and Latinas only $10.61 per hour.3

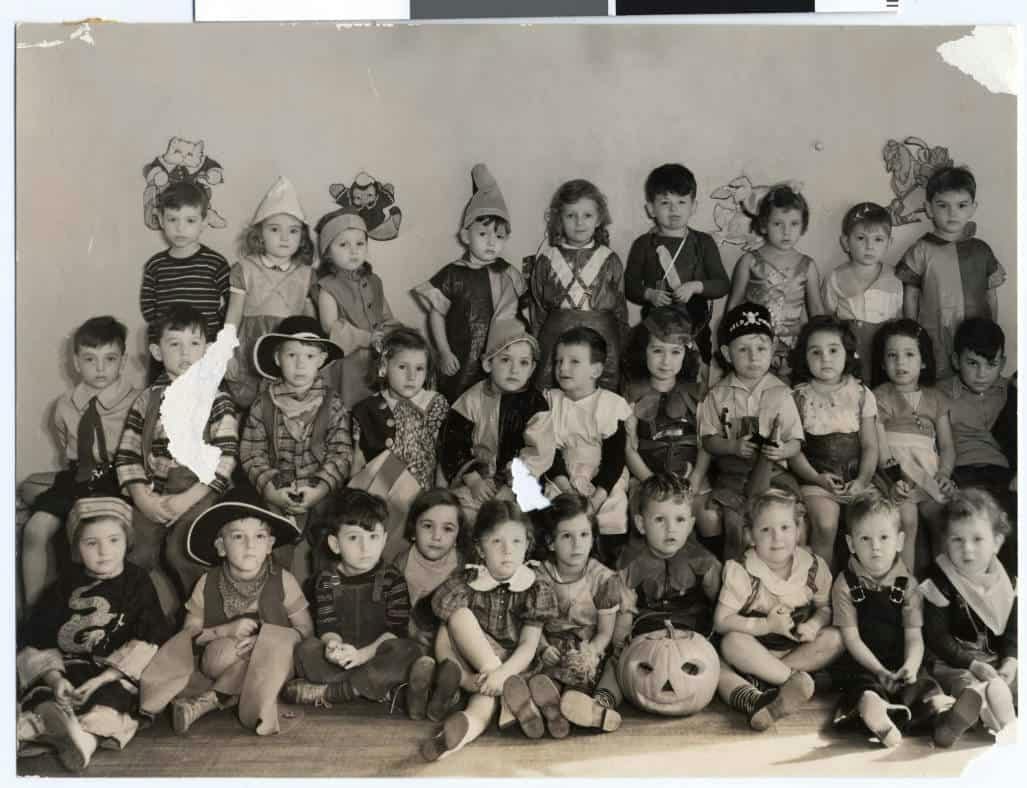

Unjust ELC Beginnings

The first policies formulizing ELC programs were deeply rooted in a white supremacy mindset, dictating eligibility for high-quality programs or family supports and creating systemic barriers based on economic, nativity, and racial designations.

In the mid-1800s, parent-funded kindergarten programs intended to “enrich and educate middle- and upper-class children,” predominantly from white families, with a child development and school-readiness focus. Yet, free kindergarten and day nursery programs for low-income families and immigrant children were “focused on teaching ‘moral habits’ based on the view that their families were incapable of properly socializing their children.”5

In the 1900s, states created mothers’ pensions based on the mindset that day nurseries were “makeshift,” a “necessary evil,” and “the mother was the best caretaker.”6 To receive funding, mothers were evaluated based on physical, mental, and moral fitness to educate their children.7 Many counties and even entire Southern states barred Black family participation. Today, families continue to face eligibility barriers to enrolling in early learning and support services, perpetuating a deficit-based and dehumanizing mindset of who deserves care.

From Understanding History to Changing It

Families and early learning and care professionals must be at the forefront of all conversations on how California reimagines an ELC system that serves all families and centers racial equity and economic justice.

We call on state leadership to scrutinize the impact of our current and proposed policies and ask:

- How will policy proposals intentionally address the roots of systemic racism that remain reflected in early educators’ treatment today? Will we eliminate the racial wage gaps?

- How will we ensure California allocates resources and programs to reach families in greatest need and farthest from opportunity?

- How will the ELC system ensure all families and children feel welcome, encouraged to participate, and valued for their assets, language, race, culture, and ethnicity?

California can respond to these questions by ensuring that the implementation of the state Master Plan for Early Learning and Care leads with a racial equity approach. We can and must begin to address the foundations of systemic racism by leading with policies, practices, and investments that advance racial equity and economic justice for our children and take care of their earliest teachers.

Advancement Project California launched our early learning and care blog series to show how California has the opportunity to take bold steps to build an early learning and care system that addresses the foundations of systemic racism, racial equity, and economic justice. Read more below, and check back daily through January 29th for new updates.

- Tracing the Roots of Systemic Racism in the US Early Childhood System

- Saving What Is Left of Early Childhood

- Daily Reality of Home-based Child Care Providers During COVID-19

- Quality Learning and Care that Women of Color Providers Bring Amidst COVID-19

- Serving Infants, Toddlers, and School-aged Children During COVID-19

- Jumping Hoops and New Ways to Show Love

- The Necessity of Staying Open During COVID-19

- Navigating an Uncertain Reality

- I Am Whole

- State and Local Resources to Support Early Learning and Care

- In-depth Supplement to the Essential Workers to the Essential Workers Blog Post Series

[1] Shiva Sethi, Christine Johnson-Staub, and Katherine Gallagher Robbins, “An Anti-Racist Approach to Supporting Child Care Through COVID-19 and Beyond,” The Center for Law and Social Policy, (July 14, 2020), https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/anti-racist-approach-supporting-child-care-through-covid-19-and-beyond.

[2] Sethi, Johnson-Staub, and Robbins, “An Anti-Racist Approach.”

[3] Claire Ewing-Nelson, “One in Five Child Care Jobs Have Been Lost Since February, and Women Are Paying the Price,” (National Women’s Law Center, August 2020), https://nwlc-ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ChildCareWorkersFS.pdf.

[4] “Transforming the Financing of Early Care and Education,” (The National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine), 46, https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24984/transforming-the-financing-of-early-care-and-education.

[5] “Transforming the Financing of Early Care and Education,” 46.

[6] “Transforming the Financing of Early Care and Education,” 46. [1] Emily Cahan, “Past Caring: A History of U.S. Preschool Car and Education for the Poor, 1820-1965,” (National Center for Children in Poverty, 1989), 20, https://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/resources/2088/pdf.

[7] Emily Cahan, “Past Caring: A History of U.S. Preschool Car and Education for the Poor, 1820-1965,” (National Center for Children in Poverty, 1989), 20, https://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/resources/2088/pdf.